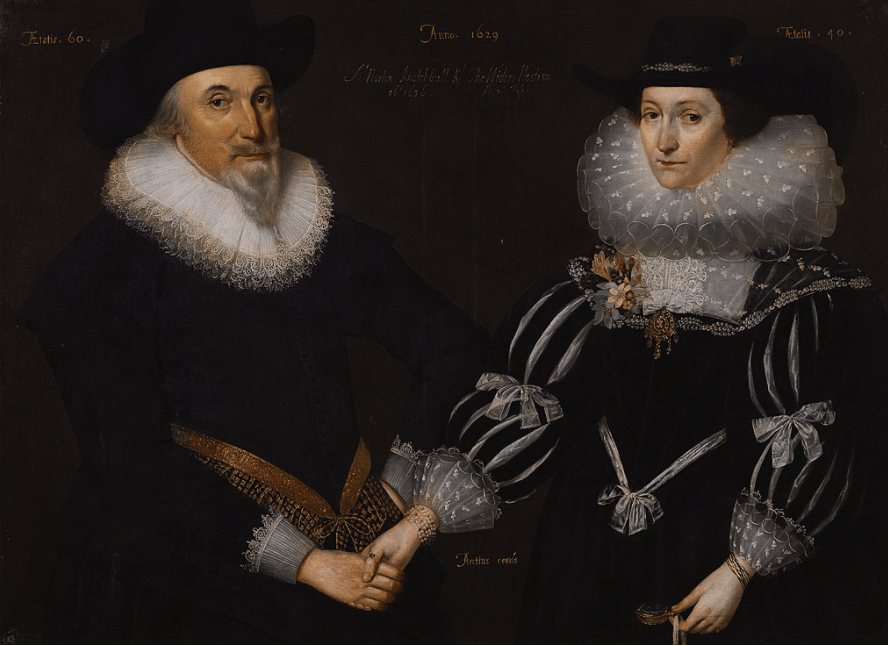

Peter Wentworth MP died in the Tower of London on his third stay there. His wife Elizabeth Walsingham, also died in the Tower a few short months before hand. She had been given permission to stay with her husband in the Tower and he described her as “my cheifest comfort in this life, even the best wife that ever poor gentleman enjoyed”. Wentworth even refused to be released from the Tower because it would be too much to be sent home to Lillingstone Lovell with memories of his wife there. He died in the Tower on 10 November 1596.

I am always a little surprised that the Wentworths died in the Tower, after all Elizabeth was the sister of Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth I’s “spymaster”. Did family count for nothing? But Sir Francis died in 1590 so could pull no strings and Peter Wentworth was his own worst enemy. He knew what would land him in trouble but carried on anyway. And I am full of admiration for him because of that.

Peter Wentworth was a thoughtful man, deliberate in what he said, and not one to pull any punches. In Parliament he raised the question of the Royal Succession, openly criticised the Queen and advocated for freedom of speech in Parliament. These were radical, maybe even treasonous, ideas especially as Elizabeth I had put in place controls over what the Commons could or could not discuss.

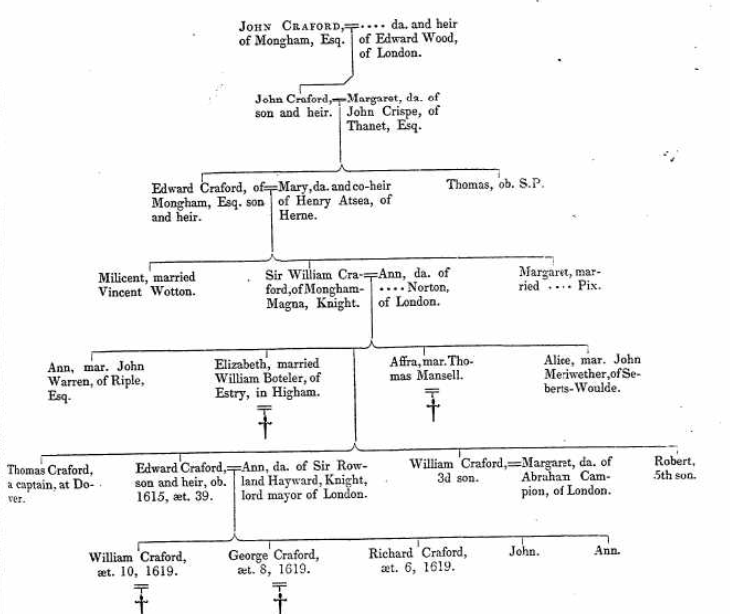

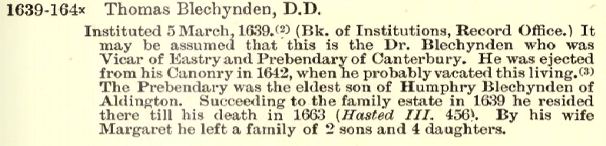

I have to admit that before digging around my family history I was not aware of Peter Wentworth or the speeches he made to Parliament and I think he deserves a wider audience, maybe a place in the national curriculum. I have mentioned in an earlier blog his connection to the Boys and Blechenden families so this one will just focus on controversial career in the House of Commons.

House of Commons, 11 November 1566

In 1566 Queen Elizabeth I had been on the throne for eight years and, aged 33, questions about her marriage and succession were rife. On 5 November of that year a delegation of 60 Lords and Commoners met with the Queen to urge her to consider the question of her marriage and the succession which provoked an angry response and on 6 November she sent a message to the Lords and the Commons that they were not to discuss the succession:

her Grace had signified to both Houses, by words of a Prince, that she by Gods Grace would Marry, and would have it therefore believed; and touching limitation for Succession, the perils be so great to her Person, and whereof the hath felt part in her Sisters time, that time will not yet suffer to trèat of it.

On 11 November Peter Wentworth questioned whether the Queen’s command to not discuss the question of her succession was contrary to the liberties and privileges of the House? The matter was debated for some time and the following day the Speaker of the House had to relay a special Command from her Highness that there should not be further talk of that matter in the House. Although the Queen later softened her approach, at least for a time, it is clear that freedom of speech in Parliament was only with Her Majesties Gracious Permission. Peter Wentworth’s questions, written in his hand, regarding the liberties of the House to free speech, have survived and can be seen on the National Archives website:

Whether hyr hyghnes’ commandment, forbyddyng the Lower Howse to speake or treate any more of the succession or of any theyre escewsses in that behalffe, be a breache of the lybertie of the free speache of the howse or not?

Wheter Mr Controller, the vicechamberlaine, and Mr Secretarye pronowncyng in the Howse the sayd commandment in hyr hyghness’ name, are of awthorytye suffycyent to bynde the howse to silence in that behalffe, or to bynde the howse to acknowledge the same to be a direct and sufficient commandment or not?

Yf hr hyghness’ said commandment be no breache of ye lybertie of the howse, or yf the commandment pronownced as afore is sayde be a suffycyent commandment to bynd the howse to take knoledge theroff, then what offence is it for anye of the howse to err in declaryng his opynyon to be otherwys?

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/elizabeth-monarchy/peter-wentworths-questions/

House of Commons, 8 February 1576

Between 1572 and 1576 Parliament was prorogued on no less than ten occasions which gave Peter Wentworth time to consider the speech that he would deliver on the first day of the new session on 8 February 1576. This is his speech that is best known amongst parliamentary orations and is credited with being the first ever full statement of the doctrine of freedom of speech in the House of Commons.

Mr. Speaker, I find written in a little volume of words these words in effect: Sweet indeed is the name of Liberty and the thing itself a value beyond all inestimable Treasure. So much the more it behoveth us to take care lest we contenting our selves with the sweetness of the name, lose and forgo the thing, being of the greatest value that can come unto this noble Realm.

He criticised the infringements upon the freedom of speech in previous sessions of Parliament and argued that without it it was just a place of “flattery and dissimulation”. It’s not hard to see why some of his fellow parliamentarians may not have welcomed Wentworth’s words:

I was never of Parliament but the last and the last Session, at both which times I saw the Liberty of free Speech, the which is the only Salve to heal all the Sores of this Common-Wealth, so much and so many ways infringed, and so many abuses offered to this Honourable Council, as hath much grieved me even of very Conscience and love to my Prince and State.

…that in this House which is termed a place of free Speech, there is nothing so necessary for the preservation of the Prince and State as free Speech, and without it is a scorn and mockery to call it a Parliament House, for in truth it is none, but a very School of Flattery and Dissimulation, and so a fit place to serve the Devil and his Angels in, and not to glorify God and benefit the Common-Wealth.

He carefully spoke about rumours and messages on what the Queen liketh or liketh not and why these did ‘very great hurt’:

Amongst other, Mr Speaker, Two things do great hurt in this place, of the which I do mean to speak: the one is a rumour which runneth about the House and this it is, take heed what you do, the Queens Majesty liketh not such a matter, whosoever prefereth it, she will be offended with him; or the contrary, her Majesty liketh of such a matter, whosoever speaketh against it she will be much offended with him.

The other: sometimes a Message is brought into the House either of Commanding or Inhibiting, very injurious to the freedom of Speech and Consultation, I would to God, Mr Speaker, that these two were Buried in Hell, I mean rumours and Messages; for wicked undoubtedly they are, the reason is, the Devil was the first Author of them, from whom proceedeth nothing but wickedness.

Wentworth, argued that only by speeking freely could they best serve Her Majesty, even if that meant suffering the Queen’s displeasure:

Then I will set down my opinion herein, that is, he that dissembleth to her Majesties peril, is to be counted as an hateful Enemy; for that he giveth unto her Majesty a detestable Judas his Kiss; and he that contrarieth her mind to her Preservation, yea though her Majesty would be much offended with him, is to be adjudged an approved Lover, for faithful are the wounds of a Lover, saith Solomon, but the Kisses of an Enemy are deceitful.

And he similarly exhorted the Queen to heed the advice of her councillors, with cricicism implied, or, rather ominously, risk the instability of her Kingdom:

And I beseech the same God to endue her Majesty with his Wisdom, whereby she may discern faithful advice from traiterous sugared Speeches, and to send her Majesty a melting yielding heart unto sound Counsel, that Will may not stand for a Reason: and then her Majesty will stand when her Enemies are fallen, for no Estate can stand where the Prince will not be governed by advice.

Unfortunately for Wentworth his arguments for the need for freedom of speech in Parliament led him to a more direct and explicit cricisism of the Queen -although he argued throughout that this was said for her own good as a faithful servant of Her Majesty:

Certain it is Mr. Speaker that none is without fault, no, not our noble Queen … Her Majesty hath committed great faults, yea dangerous faults to herself and the state … It is a dangerous thing in a prince unkindly to entreat and abuse his or her nobility and people as her Majesty did the last Parliament, and it is a dangerous thing in a prince to oppose or bend herself against her Nobility and People … and how could any prince more unkindly entreat, abuse and oppose herself against her nobility and people than her Majesty did the last Parliament? Did she not call it of purpose to prevent traitorous perils to her person and for no ther cause? Did not her Majesty send unto us two bills, willing us to make a choice of that we liked best for her safety and thereof to make a law, promising her Majesty’s royal consent thereto? And did we not first choose the one and her Majesty refused it, yielding no reason, nay yielding great reasons why she ought to have yielded to it? Yet did not we nevertheless receive the other and agreeing to make a law thereof did not her Majesty in the end refuse all our travails? And did not we her Majesty’s faithful nobility and subjects plainly and openly decipher ourselves unto her Majesty and our hateful enemy? And hath not her Majesty left us all to her open revenge? Is this a just recompence in our Christian Queen for our faithful dealings?

…It is a great and special part of our duty and office Mr. Speaker to maintain the freedom of consultation and speech for by this are good laws that do set forth God’s glory and are for the preservation of the prince and state made.

Therefore I say again and again, hate that is evil and cleave to that that is good. And this, loving and faithful hearted, I do wish to be conceived in fear of God, and of love to our prince and state, for we are incorporated into this place to serve God and all England and not to be Time-Servers and Humour Feeders, as Cancers that would pierce the Bone, or as Flatterers that would fain beguile all the World…

I particularly like the last sentence and perhaps all modern Parliamentarians should consider that they are incorporated into this place to serve God and all England and not to be times-servers and humour feeders.

Wentworth drew his speech to a close with the following although it is also suggested that he was interrupted at this point out of a reverend regard of her Majesty’s Honour and and he was stooped from proceeding before he had fully finished his Speech:

Thus I have holden you long with my rude Speech, the which since it tendeth wholly with pure Conscience to seek the advancement of Gods Glory, our Honourable Soveraigns Safety, and to the sure defence of this noble Isle of England, and all by maintaining of the Liberties of this Honourable Councel, the Fountain from whence all these do Spring; my humble and hearty Suit unto you all is, to accept my good will, and that this that I have here spoken out of Conscience and great zeal unto my Prince and State, may not be buried in the Pit of Oblivion, and so no good come thereof.

Peter Wentworth was immediately sequestered for this speech and questioned by members of the Queen’s privvy council in the afternoon of the 8th February. A transcript of the questioning remains and it is interesting to see him invoke parliamentary privilege, although he does not use that term. Parliamentary privilege is enshrined in the Bill of Rights over 100 years later: Article 9 of the Bill of Rights (1689) states “the freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in parliament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parliament” but in 1576 when Wentworth is asked about certain rumors of the Queens Majesty, he answers:

If your Honours ask me as Councellors to her Majesty, you shall pardon me; I will make you no Answer: I will do no such injury to the place from whence I came; for I am now no private Person, I am a publick, and a Councellor to the whole State in that place where it is lawful for me to speak my mind freely, and not for you as Councellors to call me to account for any thing that I do speak in the House; and therefore if you ask me as Councellors to her Majesty, you shall pardon me, I will make no Answer; but if you ask me as Committees from the House, I will make you the best Answer I can.

During the questioning Wentworth is asked to explain himself and demonstrate the truth of his speech and again and again the committee is forced to agree with him, until at last they just admit he could have phrased it better!:

Commit. Yea but you might have uttered it in better terms…

Despite this Peter Wentworth was committed to the Tower for his “violent and wicked words” on 9 February and “there to remain until such Time as this House should have further Consideration of him”.

House of Commons, 12 March 1576

Fortunately for Peter Wentworth he was not in the Tower of London for too long, as by the Queens special favour he was restored again to his Liberty and place in the House on Monday 12 March that same year. But not before he had to make an admission of his fault on his knees:

Mr Peter Wentworth was brought by the Serjeant at Arms that attended the House, to the Bar within the same, and after some Declaration made unto him by Mr Speaker in the name of the whole House both of his own great fault and offence, and also of her Majesties great and bountiful mercy shewed unto him, and after his humble Submission upon his Knees acknowledging his fault, and craving her Majesties Pardon and Favour, he was received again into the House, and restored to his place to the great contentment of all that were present.

House of Commons, 1 March 1587

In 1587 not only was the question of sucession central to Elizabeth’s reign but she was also grappling with religious turmoil which the Elizabethan Settlement had sought to address. It did not. Peter Wentworth was a puritan and was MP for Northampton, a centre of puritan activity. When in 1587 the Queen surpressed a parliamentary Bill which sought to presbyterianize the Anglican church, Peter Wentworth was ready to argue for the right to debate the matter. He prepared again a series of questions on the matter, including the one below, but the Speaker on reviewing the Articles “pocketted” them up, showed them to Sir Thomas Heneage, and Wentworth was committed straight to the Tower and the questions were not moved at all. It is unclear how long he remained there.

Whether this Council be not a place for any Member of the same here assembled freely and without controllment of any person or danger of Laws, by Bill or speech to utter any of the griefs of this Commonwealth whatsoever touching the service of God, the safety of the Prince and this Noble Realm.

One of Wentworth’s questions that were never put before the House of Commons. Simonds d’Ewes, ‘Journal of the House of Commons: February 1587’, in The Journals of All the Parliaments During the Reign of Queen Elizabeth (Shannon, Ire, 1682), pp. 407-411. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/jrnl-parliament-eliz1/pp407-411

Imprisoned again, the Gatehouse, 1591

In 1587, after the death of Mary Queen of Scots, Wentworth drafted A Pithie Exhortation of her Majestie for establishing her successor to the crowne, a tract which was given prominence when published posthumously in 1598. In it Wentworth was his characteristic blunt self. He argued strongly about the need to settle the question of the succession arguing that without this the country would be thrown into confusion and perhaps civil war with Elizabeth effectively sentencing her subjects to the “merciless bloody sword”. Drafts of the tract were leaked to the Privy Council, and in August 1591 he was once again imprisoned but this time in the Gatehouse – a prison in Westminster which stood at the front of Westminster Abbey. He was moved in November 1591 and confined in a private house before being released in February 1592.

House of Commons, 25 February 1593

At the start of a new Parliament Wentworth, returned again for Northampton, went to Westminster determined to raise again the question of the succession. Using the arguments he had set out in his Pithie Exhortation, he tried to influence newer Members of Parliament but news got out of Wentworths plans. Despite his several imprisonments he was unrepentant and remained convinced of the need to, and of his right as a Member of Parliament to, debate the matter of the succession. Peter Wentworth, together with Sir Henry Bromley, sought to obtain the support of the Lords as well as the Commons in the consideration of a Bill regarding the question of the succession. This did not go down well with Queen Elizabeth who was “highly displeased” and despite the House not sitting Wentworth, Bromey and some others were called before members of the Privy Council with Wentworth being sent to the Tower where he was to remain until his death.

Wentworth and Bromeley committed. The day after, being Sunday, and Feb. 25. and the House sat not; yet the aforesaid Mr. Wentworth, Sir Henry Bromeley, and some others, were called before the Lord Burleigh Lord Treasurer of England, the Lord Buckhurst, and Sir Thomas Henage, who intreated them very favourably, and with good Speeches; but so highly was her Majesty offended, that they must needs commit them, and so they told them. Whereupon Mr. Peter Wentworth was sent Prisoner to the Tower, Sir Henry Bromeley, and one Mr. Richard Stevens (to whom Sir Henry Bromely had imparted the matter) were sent to the Fleet, as also Mr. Welche the other Knight for Worcestershire.

For about 30 years Peter Wentworth argued for the right to freedom of speech in Parliament without limitation, without the need for the Monarch’s approval and in order to debate and perhaps help settle some of the most pressing issues of the day. He spent a number of years in the Tower of London for his pains and both he and his wife died there. Peter Wentworth was not a great politician. He was a man of conviction but he pressed ahead regardless of the almost certain consequences when perhaps a more subtle approach would have won the day. As the Committee in 1576 said “…you might have uttered it in better terms…”. But I like to think that he helped to lay the foundations for the Freedom of Speech enshrined in the 1689 Bill of Rights and which is symbolically reasserted at the beginning of every Parliament even today.